Bright Lights at Three Shadows: Shoji Ueda and Michael Cherney

John B Turner, Co-editor, PhotoForum, New Zealand, October 2018

Illustrations courtesy and copyright of Shoji Ueda Office and Three Shadows Photography Art Centre, unless otherwise noted.

|

| Three Shadows installation view of the Shoji Ueda retrospective, October 2018 |

What is it about photographic prints by Eugene Atget or Adolphe Braun or Harry Callahan or Paul Caponigro or Olivia Parker or Paul Strand or Josef Sudek or Taca Sui or Wei Bi that have the power to draw one in like a Shakespearian play or a Leonard Cohen song? They are not merely images but also objects – objects of abstract sensual beauty and intellectual intrigue. They reward intimate scrutiny of their unique specificity, their itness, but resist attempts to fully comprehend what makes them so attractive? It is this sensual, experiential and intellectual something begging to be known that excites me about seeing the work of Shoji Ueda and Michael Cherney at the same time in one place.

I don’t know what the outcome will be, but trying to put my observations into words will help me better understand what it is that sets their work above the crowd in this inspirational juxtaposition of two exceptional artists with nothing and everything to do with one another.

It is a double marriage of form and content, of real life and art, and along with Zhu Jiong’s superb Paul Caponigro retrospective at the National Fine Arts Museum in Beijing, and Three Shadows’ playful Foam exhibition of contemporary Dutch formalist photography, the Ueda and Cherney exhibitions are among the most rewarding exhibitions I have seen in China.

A note to art teachers:

These exhibitions demand and amply reward close scrutiny, so my inclination as a teacher is to urge every serious photography teacher, at any level, to book a trip for your students if you possibly can. Treat the gallery as a classroom. And encourage your students to see and discuss issues raised by these works about the nature of photography as art. My advice is to pack a lunch and take a pillow to sit on. Or ask Three Shadows to provide some seating. Encourage your students to share what they see, instead of lecturing them on what others have concluded from the works. Three Shadows can be a perfect classroom thanks to the architectural genius of Ai Weiwei, even if you have to sit on the floor. But the trick is not to look up at the work but to look directly at it. To give yourself time to figure out your feelings and thoughts about the images immediately in front of you. They are photographs of and about something – and beautiful objects as well. You might like to take a magnifying glass and torch to scrutinize the objects of your detective work. It is good fun to learn to see things we can’t see with the naked eye.

Ask the basic critical questions in the following sequence to get the most out of each picture. (Simply liking or not liking what you see is not a critical act in itself):

1. Description: what is depicted in the picture? – every detail is relevant because the photographer has already cut out the irrelevant parts.

2. Formal analysis: what are the underlying shapes, tones, colours, and textural details that form the picture and delight, repel or confuse your personal sense of visual balance or harmony.

3. Interpretation: what meaning or meanings do you get from the combination of content and form, emotionally and intellectually? Is it light or dark, serious or funny? How has size, scale, texture and colour of the printing paper affected its look and character? It’s individual itness?

4. Evaluation: On a scale of 0 at the bottom and 10 at the top, if you were the teacher, how would you rate the picture in terms of pictorial, social, historical and personal value? Would you like to own it and look at it some more? Or hate it? Or stop wasting your time and move on to something more interesting?

The good news is that unlike science or mathematics based on proven logic and experimentation, there can be no single answer when it comes to the analysis of artworks. Quite literally, one person’s failed picture can be interpreted as an exciting breakthrough, because different artists seek different answers to different questions. Each to their own.

Learning from personal investigation and experience is far more useful than remembering what others have said about an artwork, whatever the medium and product. The study of an actual photographic print, whether analogue or digital, involves confronting the final and most complete statement a photographer can make at any given time in their career, without the tactile distortions and totally out of scale digital impressions imposed by other media. (The inclusion of a dismal video representation of specific Ueda prints in the same room as the real thing at Three Shadows underlines this point, and just as inevitably, the large-screen projections of Cherney’s work seen at his artist’s talk at Three Shadows on 13 October were like dead ghosts compared to his living and deeply breathing prints in the same room.

I will start with the work of Ueda (Part I) before investigating the more complex nature of Cherney’s exploration which is going deep into the historical roots of Chinese (and Japanese) art. (Part II to follow.)

_________________________________________________________________________________

Part I: The Shoji Ueda Retrospective Exhibition

John B Turner, Co-editor, PhotoForum, New Zealand, October 2018. Illustrations courtesy and copyright of the Shoji Ueda Office and Three Shadows Photography Art Centre, unless otherwise noted.

Three Shadows Photography Art Centre, Beijing, September 23rd to November 25th, 2018.

Curated by Masako Sato. Exhibition design by Osamu Ouchi. Sponsored by The Japan Foundation with support from the Embassy of Japan in China and ANA (All Nippon Airways).

Awake or asleep, I always found myself thinking about photography. – Shoji Ueda

|

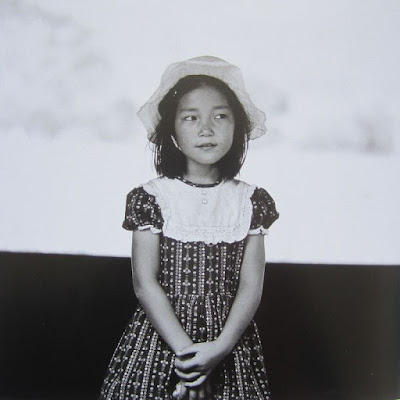

| Shoji Ueda: Our mother, 1950 |

|

| Shoji Ueda: ‘Scenery of the Dune with My Wife’, 1950 |

|

| Shoji Ueda: Portrait on the dune, 1950 |

This exhibition of nearly 140 works represents Three Shadows at its timely and relevant best by showcasing a distinctive body of accomplished work by somebody who deserves to be much better known. Somebody who takes us back in time and reminds us, as did John Szarkowski in his 1966 classic The Photographer’s Eye, that we photographers owe our understanding of the medium from every photograph we have ever seen, irrespective of the direction we may take for our own work.

Ueda was somebody who loved photography because it provided him with an emotional and intellectual outlet to enjoy and share aspects of his personal life in a space and way of his own choosing away from the demands and tragic whims of social and nationalistic political correctness. He couldn’t escape art politics altogether, and it was no coincidence that Ueda’s photographer contemporaries were happy to see him shunted out of the limelight for not being modern enough to be included on the expanding international art circuit in the 1970s when the Museum of Modern Art in New York produced the ‘New Japanese Photography’ show that spearheaded interest in Japanese photography in the West.

|

| Shoji Ueda, 1949: from series ‘The Calendars of children, 1960 |

|

| Shoji Ueda: from ‘Little biography’, 1974-1985 |

|

| Shoji Ueda: Not going anywhere, 1983 |

RongRong and Inri, the founders of Three Shadows, of course, are dedicated to doing that same necessary work for photography in China against many odds, widespread ignorance and a curious blindness to the immense cultural, social and historical value of photography as a means of communication and expression. China certainly knows how effective photography has been to propagandise its intentions and achievements, but it hasn’t woken fully to appreciate that deeply personal and honest depictions reflecting real lives and real concerns are a positive force for advancing the nation, no matter how esoteric they may appear. It remains to be seen if the digital generation, starting with their selfies, will be inspired to dig deeper and educate themselves about the work of those who use photography critically to link a personal philosophy with insight and appropriate technical skills.

Dorothea Lange (1895-1965), the great US humanitarian photographer, pinned the following quote by Francis Bacon (1561-1626) on her darkroom door to remind her that ‘The contemplation of things as they are, without substitution or imposture, without error or confusion, is in itself a nobler thing than a whole harvest of invention.’

|

| Shoji Ueda: 'Four girls Posing', 1939 |

|

| Shoji Ueda: Dad, Mom and their children, 1949 |

Shoji Ueda would have known Lange’s work because he was an avid reader of international photography magazines and art books. Looking at his work it is had to escape imagining how he might have been instructed from the published images of the likes of Edward Weston (rim light) as well as Rene Magritte and the Surrealist films of his era (props and symbols), etc. But by contrast with Lange, pictorial invention was very much a part of his repertoire and delight and helped his career in advertising and commercial photography. Actually, as he likely observed, Lange herself subtly applied a harvest of pictorial invention to her remarkably eloquent documentary photographs. Both of them knew how to use bright sunlight and strong shadows to maximum effect. The lesson from both photographers is that being true to oneself is the path to creating a distinctive signature that sets one apart from one’s peers.

|

Shoji Ueda: A Cat and Me c1949 at Three Shadows. (Photograph by John B Turner: JBT©20181013-179) |

Shoji Ueda was born in 1913, the only child of a manufacturer of traditional geta footwear, which indicates he had a comfortable middle-class upbringing. He grew up in Tottori, on the west coast of Japan facing the Korean Peninsula. Tottori is famous for its extensive 100,000 years old sand dunes and Ueda, who remained in his hometown Sanin all his life, wisely utilized them as an outdoor studio for both his personal and commercial photography.

|

| Above: crude installation copies of three family album-like photographs by Shoji Ueda from the 1960s |

As the Three Shadows introduction puts it, and his subject matter attests, Shoji was much influenced by the Western avant-garde during his adolescence. His exposure to such work came not from first-hand experience but from books and magazines, which were the common denominator for international exposure for his generation, just as electronic representations are a major source for today’s budding artists. He formed his own group rather than align himself with any of the influential avant-garde groups of his time, which to a point seems to have made him more of an outsider and in turn might have dimmed his achievement. But most of all, ‘he maintained the passionate, uninhibited spirit of an amateur’ while simultaneously running a photography centre in his hometown. ‘His intricate compositions – prime examples of staged photography – featured his family and his close friends in his neighbourhood sand dunes arranged as if chess pieces….’ In some ways his work reminds one of a big family album, not unlike the oeuvre of France’s delightfully precocious Jacques-Henri Lartigue.

|

| Shoji Ueda: Title? C.1949. This, judging by the paper stock and surface texture, might be the earliest and perhaps only vintage print in this retrospective. (JBT©20181012-118) |

Because publications rather than exhibitions were the main outlet for his work most of his photographs are small by today’s standards when digital printing has made it easy to make gigantic prints that pay no heed to optimum clarity and realistic scale. That is the main reason, along with the then relatively high cost of rationed photographic supplies in the post-war period, that the great majority of his prints are around 10 x 8 inches (25 x 20 cm), big enough for the printed page in an age of “less is more”. The international exposure given by eagerly awaited publications is also a prime reason for there being so many similarities, albeit with distinctive differences, between some of Ueda’s images and those of the likes of Angus McBean, Edward Weston, Man Ray, Harry Callahan, Phillipe Halsman, Ralph Hattersley and perhaps even Ralph Eugene Meatyard, among those with a surrealist bent. Henri Cartier-Bresson, incidentally, thought of himself as a surrealist. Today the US-born South African photographer, Roger Ballen, is a prime example of a late surrealist, as are the hordes of digital neo-surrealist dreamers vying for attention today.

|

| Edward Weston:'Civilian Defense, 1942 |

|

| Daidoh Moriyama Crippled beggar, Tokyo 1965. MoMA, New York collection |

|

| Ken Domon Children c 1955 MOMA New York collection |

Shoji Ueda’s comment that “Awake or asleep, I always found myself thinking about photography”, reminds one of psychologist Sigmund Freud’s influence, evoking an image of somebody trying to get to grips with a puzzling reality from a doctor’s couch instead of a sand dune. While Ueda’s sand dune images are featured here, I find myself particularly attracted to his delicate portraits and spontaneous images such as that of the boy pushing a calf.

As can be seen from the Three Shadows installation view below and at the head of this review, the exhibition designer Osamu Ouchi played with the surrealist theme by adding and juxtaposing ugly enlarged copies of Ueda’s images leading into the beautiful rows of distinctive and sometimes exquisite small original prints that exert their own quiet power to make us enjoy and think. The Ueda murals and the floor mats (designed to lead photo illiterates to the small originals) were attractive decorations and worked well - to a point. But like the dismal grey videos on display, they were more likely to distract visitors from discovering for themselves the special delights of the main meal. Furthermore, nobody had bothered to remove the ugly dust spots that the majority of self-respecting modernist photographers would have retouched to prevent that visual static from shattering the seamless illusion of three dimensions they had painstakingly crafted.[i]

This lapse in curatorial control with Ueda’s retrospective came as a bit of a shock because it was so obviously contrary to the understated delights of the photographer’s intention. On closer inspection, while trying to figure out exactly what kind of printing paper the photographer had used, I could see that some prints looked like unspotted “seconds”, prints that had not been finished for presentation for either an exhibition or publication. Was their inclusion a curatorial lapse? Or had the dyes or possibly pigment used to “spot” out the visual static faded over time? As they are, the dust-marked images are out of tune with the delicacy of the majority of the works on display. If so, in keeping with the artist’s sensibility, the simple remedy would be to restore them for re-presentation.[ii]

I could detect only three kinds of papers used by Ueda: two, the majority of them had a fairly high-gloss texture with one slightly more fibrous than the other. A possibly third and lightly textured paper was used for his lovely image of a woman and two children (his family?) standing in the snow (see illustration above). It is not mentioned when his actual prints were made but the fact that they are virtually all on what looks like a glazed gelatin silver print surface of the kind that was commonly used for reproduction in publications rather than exhibition because of its surface sheen. There are always exceptions, of course, such as Brassai who glazed his large exhibition prints, but this does raise the question not just about when Ueda’s prints were made and what they were made for? My sense is that these prints of his images made from the first three decades (the 1930s to at least the 1950s) were made around the 1960s or perhaps later? And as I write I am waiting to hear from the curator, Masako Sato, for her confirmation.

My facebook letter to curator Makato Sato:

‘Dear Ms Sato, I am reviewing the wonderful Shoji Ueda retrospective at Three Shadows and would like to know when the actual prints exhibited were made. I could detect two different print surfaces and possibly a third one which indicates they are gelatin silver prints, but I'm not certain if any were made about say 1947 (the dates given). And being essentially glossy (probably glazed) they have the appearance of prints made for reproduction rather than specifically for exhibition. I suspect that some were made later, rather than earlier, possibly in the 1970s or even later. My other question relates to the fact that some of the exhibited prints are not spotted, which suggests either that they were never exhibited or used for publication; or that if spotted, which surely a man of his refined sensibility would do, perhaps the spotting faded (if he used dyes instead of the pigment cakes that were not suitable for glossy prints)? Your help would be very much appreciated. Kind Regards, John B Turner. [No answer has been received as of 1 November 2018]

No matter what, this is a major exhibition by a significant practitioner who had the foresight and finances to bequeath his own museum to preserve and promote his delightfully impressive legacy.

– John B Turner, Beijing 1 November 2018. (www.jbt.photoshelter.com)

|

| John B Turner: Installation view of the Shoji Ueda retrospective at Three Shadows Photography Art Centre, Beijing, October 2018 |

|

| Display of Shoji Ueda’s published work at Three Shadows Photography Art Centre. (JBT©20181012-108) |

Note: The following video has just been uploaded to Youtube: ‘He Took Pictures of Naked Women, His Wife and Sons and Celebrities in Countryside for All His Life’:

Contact details:

Three Shadows Photography Art Centre, Caochangdi 155A, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100015, P.R. China. Email: info@threeshadows.cn. Phone: 86-10-64322663.

Website: www.threeshadows.cn

Open every day except Mondays

[i] Fortunately, this designer, unlike one at the Pingyao International Photography Festival of a few years back, did not resort to flooding the gallery with sand and driftwood to prove beyond doubt what sand and weather-worn dead trees actually look and feel like. But he neglected to add the naked bodies in the sandy landscape or ask the audience to take off their shoes to feel the sand.

[ii] This lack of respect towards the practice and intention of the photographer was very much in evidence in Three Shadows important historical survey, ’40 years of Chinese contemporary photography’ of 2017, in which it was clear that many of the actual prints exhibited had never been finished either for exhibition or publication but were the only examples available. It’s a tricky issue, but displayed and published without at least spotting out the obvious dust marks, the prints on display did nothing to justify their inclusion among provably accomplished peers, let alone enhance their maker’s reputation and that of Chinese photography on a world stage. Whatever is done or not done the important thing is that it is transparent so there is no doubt in the viewer’s mind as to the state and context of work presented. That was not done and consequently undermined both the integrity and historical value of the enterprise.

No comments:

Post a Comment