Seldom has the name of an event been so apt as that of the Central Academy of Fine Arts Art Museum (CAFAM’s) ‘Confusing Public and Private,’ the title of the belated 3rd Beijing Photo Biennial, but not in the way intended.

|

| Viviane Sassen (Netherlands). Installation detail |

WARNING: PR DISASTER AHEAD!

CAFA Art Museum has a public relations problem. I contacted them several times last year to ask for

information about their due third Photo Biennial. I wanted to participate and help publicize it. The first and second biennials, in 2013 and 2015 were international in scope, with challenging contemporary work of a higher standard than the many token “international” photography events that I have seen in China. They also had a top lineup of practitioners and academics to discuss topical issues.

Nothing, nothing and nothing came from my web searches and direct inquiries to CAFAM, and nowhere could I find any notice that the 3rd Photo Biennial had been canned or postponed.

I later learned that the head of the Museum, Wang Huangsheng, who is known as a shaker and mover in the art scene had moved on. But there was no news of the expected biennial which I feared had been starved to death. Nobody I asked at the October 2017 International PhotoBeijing week, with which the first CAFA biennial was linked, nor my other contacts could tell me why the most exciting photography event in Beijing had simply disappeared from the calendar?

My early inquiries this year bore no fruit until I met Cai Meng, a curator of CAFAM, at Three Shadows Photography Art Center a month ago. He confirmed that the 3rd Biennial was going ahead but failed to deliver on sending me the information about it. I don’t doubt that he is busy or very busy, because the biennial is such a huge undertaking, but the habitual lack of advanced PR notice, support and follow up in China is beyond a joke. (And I’m not just referring to the occasional English translations.)

|

| Shen Xuezhe (China) |

To make things worse, the typically last-minute press release was both confusing and wrong – as was the verbal assurance from my phone call to the CAFAM office that my visiting New Zealand photographer friend, Julian Ward, and I could see the exhibition just before its announced opening at 5pm on 28 September. They got it wrong. There was building going on but no show when we turned up. The front desk staff told us that the show was due to open on 1 October, China’s National Day instead and it was left to a lovely and helpful curatorial intern to apologize profusely on behalf of the museum. She earnestly promised that they would send us a book as compensation for wasting our time and taxi fares, but I seriously doubt the Museum will deliver.

Jayson, the new manager of the museum’s coffee bar, who had spent 15 years in Australia, recognized our accents and went out of his way to chat and smooth over the museum’s PR cock-up, even though he had nothing to do with the show.

|

| Léonard Pongo (Belgium) |

There was another problem with the lack of information. To further confuse matters, the show was

unevenly split between two venues nearly 500 kilometers apart it had two different names, no facts as to exactly when or where it was opening, nor anything about the academic seminars which usually

accompany the biennial.

I wanted Julian Ward, who had exhibited some of his India photographs at the recent Pingyao International Photography Festival, to see how impressive CAFAM’s biennials could be, so after another phone call to them we went back on 3 October, his last day in Beijing. There we learned how monumental the 3rd biennial’s split personality had become. Only a small part of it is displayed in the CAFA Art Museum at No.8 Huajiadi South St, Chaoyang, Beijing 100102, taking up about half of its ground floor and a little easy-to-miss mezzanine above it. To see the rest of it, the very private public part, requires a four-hour trip to Beizhen, 490 kilometers away in Liaoning province, northeast China.

CAFAM may be taking long distance learning very seriously, but despite an impressive lineup of exhibitors and all but two of the Chinese contributors showing at Beizhen, I’m not sure that I can be bothered to go that far to see the rest of the show.

|

| Mário Macilau (Mozambique) |

The poster for the Beizhen exhibition bills it as ‘Troubled Intentions Ahead: Confusing Public and Private,’ as part of the 2018 Beizhen China Ist International Photography Festival, 28 September to 28 October 2018’ It is sponsored by the Culture Industry Center of Beizhen Jinzhou, Liaoning. (No place, address, contact number or GPS location is given.) CAFAM’s 3rd Beijing Photo Biennial (minus ‘International’) is given a minor billing with the dates 1 October to 4 November. Beizhen has trumped CAFAM, it seems, but it is not clear if the shows are one and the same? CAFAM bills its mini-show as just ‘Confusing Public and Private’. A second publicity sheet reclaims the Beizhen exhibition for CAFAM, as the overall organizer of this chaos with Chinese characteristics, when what is needed is hard facts and consistency.

For the record, one can see work by the following practitioners at CAFAM: Berna Reale (Brazil); Bruno Morais & Cristina de Middel (Brazil and Spain); Shen Xuezhe (China); Eddo Hartmann (Netherlands); Eva O’Leary (USA); Léonard Pongo (Belgium); Mário Macilau (Mozambique); Pieter Hugo (South Africa); Viviane Sassen (Netherlands); Weronika Gesiscka (Poland); Richard Mosse (Ireland), and Yu Xunling (China). That’s 12 of the 112 artists listed. A lineup which includes Erich Von Stroheim, Gerhard Richter, Marcel Duchamp, MC Escher, Man Ray and Robert Frank among the most famous of the famous whose work is virtually out of reach.

The Curatorial Committee (of the 2018 Beizhen International Photography Festival) is listed as Fan Di’an, Wang Huangsheng, Zhang Zikang, Hans de Wolf, Cai Meng, Ângela Ferreira and He Yining. Although written in the first person, the author of the extensive wall texts is not identified.

|

| Vivien Sassoon (Netherlands) |

The idea of private photography going public is not new anymore than is the juxtaposition of work made for the public displayed with more intensely personal work, so the stated catch-all rationale seems like flimsy academic window dressing to me. Here are some samples:

‘As a new form of technology, medium, and application, photography has been associated with issues concerning the public vs. the private since the day it was invented.’ [What? How new is new? Photography will be 180 years old next year!]

|

| Bruno Morais & Cristina de Middel (Brazil and Spain) |

‘From the inherently private practices of shooting and displaying in public spaces in the early days of photography,’ it continues, ‘to the democratization of image in today's world of camera phones, mobile web, and social media, and the constantly evolving visualization of data in contemporary art, photography has become an important medium that extends, interferes, participates in the construction of public and private lives to an ever-increasing degree. As a result, the public and private elements of photography continue to integrate and spread from constant clashes and

confrontations between real and fictional spaces; they are also changing our modes of expression, relationships and behavioral patterns while filling up our public and private living spaces. Eventually, with the extensive photography interference, public and private spaces are reconstructed, as are the boundaries between the individual and the community and the definitions of self and others. During this metamorphasis [sic.], photography becomes intertwined and resonates in new ways with a variety of important factors such as history, reality, religion, philosophy, civilization, war, science & technology, politics, and human emotions. As a medium or a bridge between different worlds, its

performance unfolds in both the public sphere and the private sphere. In a spatial-temporal context where the public and the private are merged, the modes of organization and thinking are extremely complex, and the atmosphere is characterized by a sense of ritualism and absurdity: how can we embark on an adventure of the mind? What kind of world is this? How is it related to us? In an intellectual field of visual drama that could be defined as Utopia, Dystopia, Heterotopia or Protopia, the way we tackle the relationship between the public and the private and its expressions via

photography will be the common goal we build on a comparatively broader, higher and more distant point of view, and it will also become our curatorial starting point for the exhibition. Therefore, the exhibition revolves around the complex coexistence of the social, public, and private characteristics of photography—a broad, multidisciplinary field—and explore[s] photography[s] role and significance in the tension between the public and the private.

|

| Bruno Morais & Cristina de Middel (Brazil and Spain) |

`It is worth pointing out that, by drawing on past experience and learning from the challenges we faced during the first two biennials, the curatorial team has designed the exhibition with an experimental and daring organizational method based on the theme "Confusing Public and Private", with the hope of presenting a completely different kind of show this year.’

“Daring and more experimental”? Yes, if the experiment is to prevent people from seeing the whole show? Or are they referring to more design acrobatics and window dressing? Actually, to be fair, most of the work, tucked into the adapted packing crates with their own lighting, is well displayed, except for the occasional blur of light in one’s eyes.

|

| Eva O’Leary (USA) Installation and video detail (below) |

|

| Pieter Hugo (South Africa). Photographs from China |

Better late than never, the ‘Mission & Purpose’ of this event is spelled out in one of the large wall posters. Later still will come a publication, one hopes, that will marry the contents of the split venues and rationalize the wordy justifications.

‘The Beijing Photo Biennial has received wide attention and recognition in the art industry and related fields following the success of its first two editions ("Aura and Post-Aura", 2013 & "Unfamiliar Asia", 2015 [link here]. As one of CAFA Art Museum's signature events, the project aims to examine the ways photography—with its unique form of interference and application and a constantly self-renewing medium—continues to engage in contemporary cultural narratives and the construction of new artistic orders and structures. Drawing on Western classics and cutting-edge photographic resources around the world while keeping an eye on the future, we hope to discover and support talented young photographers in China and encourage them to explore the language of photography, expand their views, and contribute to the development of photography by bringing the influence and prominence of Chinese contemporary photography to another level in the global art industry.’

‘This year's biennial is featured as part of the Special Exhibitions section of the 1st Beizhen International Photography Festival and will be held simultaneously at the Culture Industry Center of Beizhen and the CAFA Art Museum. The exhibition will showcase close to 1000 works by some 112 artists from around the world, accompanied by a series of seminars, forums, talks and public educational events. The CAFA Art Museum continues to bring advanced modes of thinking and organization from contemporary culture and the art industry into the field of photography and lens-based media in China, with the aim to enhance its cultural depth, academic scope, quality of communication, and globalized vision. By presenting photography as a universal, contemporary, practical and everyday medium of visual expression, we hope to reveal the specialized and in-depth reflections of contemporary photographers and artists on subjects such as history, social reality, art and the self, while inspiring more people to discover, explore, and reexamine this unique medium. At the same time, we also want to explore a new kind of curatorial system that puts emphasis on the social and public roles of university art museums by collaborating with the local government in order to contribute to the development of those regions that are still in state of developing culturally, as well as to expand the platforms for art and cultural exchange in a new era.’

|

| Joan Fontcuberta (Spain) |

In other words, the political expediency of presenting CAFA’s 3rd Biennial demanded that most of it would not be seen in its home town. ‘Troubled Intentions Ahead: Confusing Public and Private.’ Indeed. This looks like another case of government and private institutions just ticking the boxes for their patron bureaucrats and makes no sense in terms of drawing the kind of audience one would expect from the capital’s diverse groups of academic and non-academic punters. Art school students are not tourists so it is unlikely that any of Beijing’s art schools will transport their students to Beizhen to study what should be an important collection of photographs, let alone critique the curatorial muddle. More’s the pity, and I for one am curious to see how the work of a large number of Chinese photographers’ fare in the company of the well-known foreign practitioners picked for this show?

There is an awful lot of pretentious “art photography” in the world these days with much of it screaming “Look at me, aren’t I clever” in the way that fashion and advertising photography turns all kinds of tricks to gain attention. But more, perhaps, on that later?

|

| Weronika Gesiscka (Poland). Full frame and detail from image |

|

| Eddo Hartmann (Netherlands). North Korea |

My New Zealand visitor was not particularly impressed by what he saw and neither was I. Of the work of about 10 photographers on show the standout work for me was Richard Mosse’s large screen triple-image video literally combining negative and positive imagery, and possibly infra red, of and related to the flood of immigrants to Europe on and off the sea. It was an eerie dream-nightmare-like combination with a dramatic soundtrack. Julian, an accomplished filmmaker and producer, was less impressed. Rather than comment on individual works, my intention is to go back again and check my first impressions of this addenda to the unseen show in Beizhen city.

Here is the full 3rd Beijing Photo Biennial Artist List outed on 27 September 2018:

Aby Warburg (Germany); Aristotle Roufanis (Greece); Anni Hanen (Finland); Anna Fox (UK); Andrea Eichenberger (Brazil); Ariane Loze (Belgium); Berna Reale (Brazil); Bruno Morais & Cristina de Middel (Brazil and Spain); Broomberg & Chanarin (South Africa and UK); Barbara Probst (Germany); Beni Bischof (Switzerland); Chen Baoyang (China); Chen Haishu (China); Catrine Val (Germany); Claudia Andujar (Brazil); Candida Höfer (Germany); Catherine Balet (France); Carl Johan Erikson (Sweden); Dai Xianjing (China); Daniela Friebel (Germany); Dagmar Keller (Germany ); David Claerbout (Belgium); Dirk Braeckman (Belgium); Edgar Martins (Portugal); Eddo Hartmann (Netherlands); Emmanuel Van Der Auwera (Belgium); Eva O’Leary (USA); Erich Von Stroheim (Austria); Eleazar Ortuño (Spain); Gong Baoming (China); Guo

Guozhu (China); Gong Yingying (China); Gao Yan (China); Galit Seligmann (Israel); Gayatri Ganju (India); Gerhard Richter (Germany); Giuseppe Penone (Italy); Gisela Motta and Leandro Lima (Brazil); Hao Jingban (China); Hu Weiyi (China); Honoré d’O (Belgium); Ji Zhou (China); Jeff Wall (Canada); Joan Fontcuberta (Spain); Jewro Roppel (Kazakhstan); Jan Vercruysse (Belgium); Jo Ractliffe (South Africa); Letícia Lampert (Brazil); Laura Quiñonez (Colombia); Laura Pannack (UK); Luigi Ghirri (Italy); Latif Al Ani (Iraq); Lua Ribeira (Spain ); Léonard Pongo (Belgium); Alexvi (China); Li Lang (China); Li Longjun (China); Lv Jiatong (China); Luo Jing (China); Li Yong (China); Liu Zhang Bolong (China); Ma Haijiao (China); Marcel Broodthaers (Belgium); Marcel Duchamp (USA); Malick Sidibé (Mali); Martin Bollati (Argentina); Mário Macilau (Mozambique); Man Ray (USA); M.C. Escher (Netherlands); Mathias LØvgreen & Sebastian Kloborg (Denmark); Natasha Caruana (UK); Ke Peng (China); Patrick Faigenbaum (France); Pieter Hugo (South Africa); Rochelle Costi (Brazil); Roger Ballen (USA); Rosa Gauditano (Brazil); Richard Mosse (Ireland);

Rosângela Rennó (Brazil); Robert Frank and Laura Israel (Switzerland and USA); Song Dong (China); Shen Linghao (China); Su Jiehao (China); Shen Xuezhe (China); 宋兮 Song Xi (China); Song Ziwei (China); Sarah Mei Herman (Netherlands); Sara, Peter and Tobias (Danish); Shizuka Yokomizo (Japan); Shen Wei (USA); Taca Sui (China); Todd Hido (USA); Vanja Bucan (Slovenia); Viviane Sassen (Netherlands); Weronika Gesiscka (Poland); Wolfgang Laib (Germany); Wang Penghua (China); Wang Haiqing (China); Wang Tuo (China); Wang Yishu (China); Wang Zhengxiang (Taiwan China); Weng Fen (China); Wei Lai (China); Xu Bing (China); Xu Xiaoxiao (China); Xu Hao (China); Yang Fudong (China); Yang Yuanyuan (China); Yu Xunling (China); Zhang Jungang (China); Zhang Jin (China); Zhang Xiao (China); Zhang Yongji (China).

It appears that new tariffs on South Pacific and Southern Hemisphere practitioners in particular, along with the Russians, have once again prevented their inclusion in this international event. Maybe some other time ….? In the meantime, you can get some idea of what is on display at CAFAM from my rough installation shots interspersed throughout this report.

|

| Richard Mosse (Ireland). Projected video |

|

| Richard Mosse (Ireland). Projected video (details) |

|

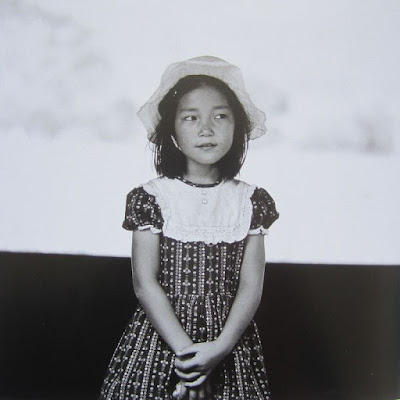

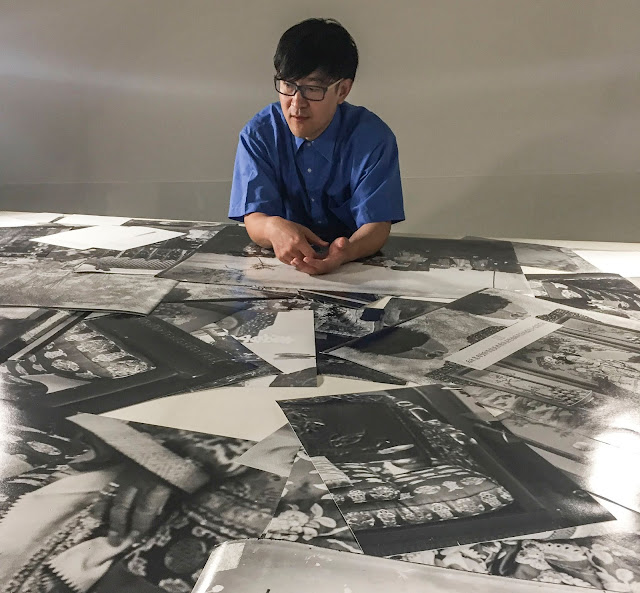

| Yu Xunling (China). Portraits of Xixi, Empress Dowager of China, c.1900 |

|

| Cai Meng, CAFAM curator with copies of details from portraits of Xixi, Empress Dowager of China, c.1900 by Yu Xunling (China) purchased from the Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, USA. |

|

| John B Turner inspecting copy prints of Yu Xunling's portraits of Xixi, Empress Dowager of China, c.1900. Courtesy of CAFAM |

Endnote

CAFAM’s ‘Confusing Public and Private,’ 3rd Beijing Photo Biennial exhibition is scheduled to be on until 4 November 2018. CAFA Art Museum, No.8 Huajiadi South St, Chaoyang, Beijing 100102. www.cafamuseum.org

The Beizhen show finishes on 28 October 2018. Their only physical address is given as Liaoning Beizhen Cultural Industry Center, Beizhen, Liaoning.

The following link will take you to CAFAM’S press releases in Chinese: https://www.sohu.com/a/257917193_422774. When opened in MS Word just right-click “Translate” to read the items in English or another second language. Then save it as a PDF for your archive.

POSTSCRIPT

The 2018 Beizhen China Ist International Photography Festival, incorporating CAFAM’s 3rd Beijing Photo Biennial is over and I for one did not get to the tourist town of Beizhen to see it. Instead, I met Shi Chun, a member of the curatorial group at PhotoBeijing on 21 October. He confirmed my hunch that it was a governmental decision to take funds from CAFAM to pay for Beizhen’s first festival, and promised to send me the Beizhen/CAFAM catalogue and promply did so. (The books promised by CAFAM to Julian Ward and myself for misleading us about the opening of their minor chunk of the Biennial have never arrived, however.) As to the fate of the announced Academic Forum, the programme was spelled out in the catalogue – but it never happened because no money was allocated for it.

CAFA never bussed its students to Beizhen, I was later told, but some of the Beijing-based academic fraternity did attend the opening. It would be interesting to know what the attendance records were for the Beizhen festival, and what critical coverage it might have attracted? But I’m not holding my breath over this administrative misadventure which left CAFAM in the lurch.

This lost opportunity has not only done a disservice to the herculean efforts of its premier art school to build on the growing reputation of what promised to be a continuing event of truly international stature, but has also undermined Beijing’s claim to be recognized worldwide as China’s cultural capital.